In a recent circular, CBSE has instructed its affiliated schools to put their staffing reality on record: upload and regularly update complete teacher details and related information on the school website under Mandatory Public Disclosure, in the prescribed format, by 15 February 2026.The compliance message is clear. This is not a polite nudge towards transparency. CBSE says schools have been lax and sloppy with disclosures, and it warns that missing, incomplete or incorrect information can trigger action under the Affiliation Bye-laws—turning staffing from an internal file into a public, enforceable condition of affiliation. The message is very clear: Staffing adequacy will now be visible, verifiable and contestable. A school website is being recast as a compliance document, not a marketing brochure. Once staffing is forced into the open, the next question is unavoidable: not what the system’s averages look like, but where the teachers actually are—and where they aren’t. Official data continues to suggest that India, on paper, maintains a comfortable pupil–teacher ratio. Yet the same system struggles with uneven teacher deployment, vacancies and subject-level gaps that the ratio alone fails to capture.

CBSE spells it out: 30:1 PTR , 1.5 teachers per section and penalties for fudging the math

CBSE’s circular does not leave PTR open to interpretation. It states that the pupil–teacher ratio should not exceed 30:1 in schools. The Board then adds a second, stricter staffing check that schools can’t dodge with creative averaging: There must be 1.5 teachers per section, excluding the principal, physical education teacher and counsellor, “to teach various subjects”.Why the hard tone? CBSE records that despite repeated directions, schools are not updating information at regular intervals, or are uploading incorrect details or invalid documents under “Mandatory Public Disclosure”. Teacher details and qualifications, it notes, are “invariably” missing from many school websites.The compliance clock is explicit: Schools must put the required information online in the revised Appendix IX format latest by 15 February 2026. And the sting is at the end: Non-compliance will be viewed seriously as a violation of Clause 12.2.3, which may lead to penalties under Chapter 12 of the CBSE Affiliation Bye-laws—i.e., formal action that can escalate from warnings and restrictions to harsher measures for repeat or serious breaches.

India’s PTR looks comfortable until the state map is unfolded

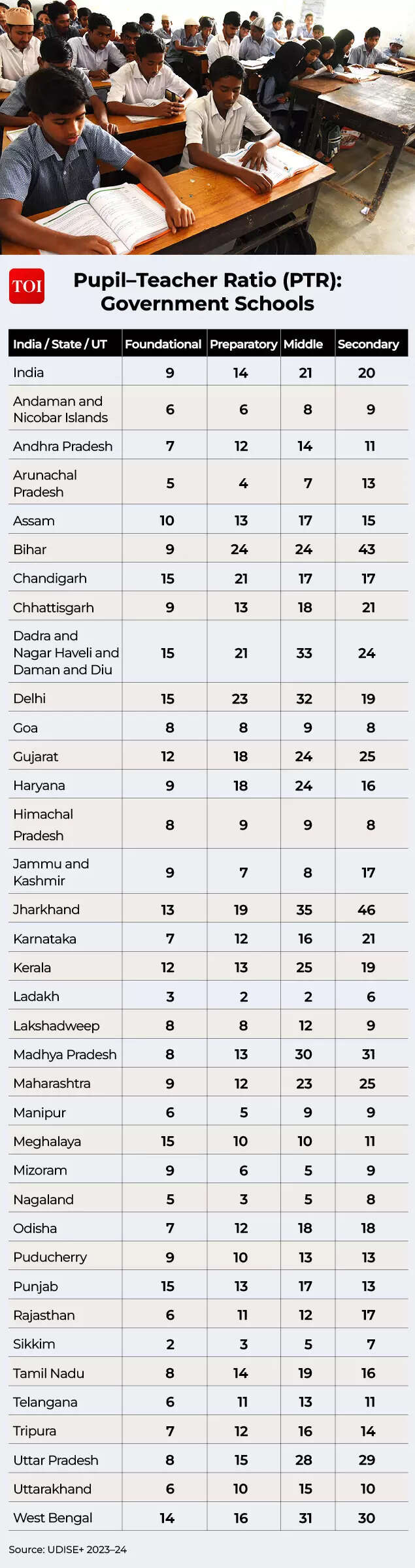

At the national level, India’s pupil–teacher ratio appears firmly within the comfort zone. According to a Lok Sabha reply answered on 10 February 2025, the government told Parliament that PTR in government schools stood at 9:1 at the foundational stage, 14:1 at the preparatory stage, 21:1 at middle school, and 20:1 at secondary level, based on UDISE+ 2023–24 data. Read in isolation, these averages suggest a system that has, at least numerically, moved past the era of overcrowded classrooms.But the same official table tells a less comfortable story once the national figure is disaggregated by state and stage. At the secondary level—the most staffing-intensive segment—Bihar records a PTR of 43, Jharkhand 46, Madhya Pradesh 31, Uttar Pradesh 29, and West Bengal 30. Middle-school PTRs also spike sharply in several large states, with Delhi at 32, Jharkhand at 35, and West Bengal at 31.

State-wise pupil–teacher ratio (PTR) in government schools

The implication is hard to miss. India’s PTR problem is no longer one of national scarcity, but of where teachers are concentrated, and where they are thin on the ground—especially in upper grades where subject availability matters most. Averages reassure while state-wise distribution unsettles. This is precisely the gap CBSE’s disclosure push begins to expose.

Beyond PTR: 1.5 teachers per classroom exposes the gaps

CBSE’s 1.5-teachers-per-classroom requirement exposes the governance problem that PTR averages routinely conceal: distribution. A system can report acceptable national ratios and still host structural understaffing at the school level. The government itself has acknowledged this distribution strain: A Rajya Sabha reply on 03 December 2025 states that UDISE+ 2024–25 records 1,04,125 single-teacher schools. In these schools, “1.5 teachers per classroom” is not a target — it’s a different universe. One teacher ends up teaching multiple grades, plugging subject gaps, handling registers and mid-day logistics, and still being expected to offer attention that a child can learn from. It is less a classroom and more a survival unit.In such contexts, compliance becomes mathematically impossible and pedagogically fragile. The issue is less the national stock of teachers and more recruitment, deployment and vacancy-filling—functions that the same Rajya Sabha reply locates primarily with States/UTs.The contradiction is stark: a national policy architecture built around adequate ratios, and a ground reality where distribution failures leave entire schools functionally under-staffed. CBSE can demand staffing adequacy, but the distribution gap leaves too many schools stretched thin. In that light, the 1.5-teacher rule is not bureaucratic fussiness — it is CBSE putting a torch to the places where the average stops working.

Transparency is the trigger , not the fix

CBSE’s disclosure push is a useful correction: It turns staffing from a private claim into a public record. But disclosure cannot substitute for deployment. Uploading teacher data may expose gaps and deter creative accounting, yet it cannot fill vacancies, redistribute staff, or repair subject-wise shortages that sit outside a school’s website and inside the state’s recruitment and posting machinery. The real test begins after 15th February 2026. What remains to be seen is whether enforcement is steady enough to make staffing norms consequential, and whether states respond with time-bound appointments and rational placement. In other words, transparency can make the problem visible. Solving it will still require the boring, difficult work of governance.